Have you ever been to a meeting so important that it will be remembered and celebrated 17 centuries from today? If so, would you even know?

As a pastor of local congregations, I often liked church council meetings. When they worked well, council meetings could be an act of worship: gathering in Christian community, remembering who we are as God’s people, and discerning how God is calling us to proclaim the timeless Christian story in our particular social and historic location. But I am no Pollyanna; I have participated in many church meetings where parking lot alliances carried into the conference room, debate descended into competing factions, and tempers flared nearly to the point of coming to blows (and if you believe the hearsay, a punch or two was actually thrown!).

Like most modern church council meetings, the First Council of Nicaea consisted of pure and impure motives, Spirit-led debate and human-centered conflict, internal and external political undertones, and salacious rumors from people who were not actually “in the room where it happened.” This months-long meeting in 325 C.E. was a relatable mixture of worship and woe, which might be why it still captivates, provokes, and influences us today as Christians.

The Nicene Creed as A Communal Story

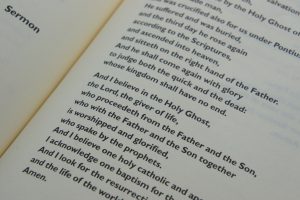

The most enduring influence of the First Council of Nicaea is the development of the Nicene Creed, which is still recited widely in weekly worship and sacramental rites and taught and memorized in confirmation classes or catechesis. The creed, says Luke Timothy Johnson, is not so much a philosophy of life as it is a story that answers the primary questions of human identity: Where do you come from? Who are you? Where are you going?[1]

Unlike most earlier creeds, the Nicene Creed is deliberately communal. It is not about what “I believe” but rather about what “we believe” as a community. The creed professes shared convictions, sets the boundaries of Christian belief, and enables us to affirm the central narrative of our faith. In other words, it answers the deep questions of identity posed by Johnson:

Where do we come from?

We come from God, maker of all things visible and invisible.

Who are we?

We are followers of the one Lord, Jesus Christ, who for our salvation was incarnate, crucified, rose from the dead, and ascended into heaven, and calls us into one baptism for the forgiveness of sins and into one holy, catholic, and apostolic church.

Where are we going?

We seek to share in Christ’s resurrection and in the world to come, God’s everlasting kingdom on earth as it already is in heaven.

An Enduring Ecumenical Connection: the Gospel as Our Formative Narrative

It is no accident that the Council of Nicaea is most known for the communal creed it produced. Christological debates at the time threatened to fracture the church into many disputing religious communities rather than a unified body of believers. In what can only be described as a miracle of the Holy Spirit, more than 200 bishops were assembled by the Roman emperor, wrote a creed by committee, and settled disputes standing in the way of ecumenical cooperation. And though our human fallibility could not avoid schisms in the succeeding 1700 years, the creed continues to be an ecumenical thread that can pull together the patchwork quilt of Christian traditions. It can do this because the creed proclaims the story of our shared faith.

Stanley Hauerwas believes in the power of story to orient us in communities of moral formation. We need to be “introduced to stories that provide a way to locate ourselves in relation to others, our society, and the universe,” he says.[2]

The problem, he argues, is that rather than orienting our lives and identities around a single community and its narrative, we belong to too many competing communities forming us in divergent ways. The Christian task is to be faithful to the story of the gospel as a primary and coherent narrative. Hauerwas writes, “The story of God does not offer a resolution of life’s difficulties, but it offers us something better—an adventure and a struggle, for we are possessors of the happy news that God has called people together to live faithful to the reality that he is the Lord of this world.”[3]

A Shared Adventure

Our world is not much different than the one in which the First Council of Nicaea convened. We too have a church and world rife with human differences, religious schisms, and powerful political dynamics. But when we rise in worship and recite the Nicene Creed, we are not simply repeating old words written long ago and passed on to us through the centuries. The creed proclaims our choice of narrative to orient us in a divided and chaotic world: a story that reminds us where we came from, who we are, and where we are going. And whatever differences we may have with the Christian across the aisle, across the street, or across time and location, we are happily called into a shared adventure and struggle. It matters not whether we are remembered 17 centuries from now, nor whether we ever came to blows over Christology, but whether God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is glorified by how we live. Amen.

[1] Johnson, Luke Timothy. The Creed: What Christians Believe and Why It Matters (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 59.

[2] Hauerwas, Stanley. A Community of Character: Toward a Constructive Christian Social Ethic (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981), 148.

[3] Ibid., 149.

The Rev. Erik Hoeke is an ordained elder in the Western Pennsylvania Conference of The United Methodist Church and the director of continuing education at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Previously, Erik served United Methodist churches in Southwestern Pa. for 14 years. He earned a B.A. in English/journalism from Ohio Northern University, a master of divinity from Candler School of Theology in Atlanta, Ga., and a master’s in moral theology from Boston College. He currently serves on the board of directors for Jumonville Camp and Retreat Center in Hopwood, Pa., and has previously served on various boards and committees for the UMC and for nonprofits. Erik also has experience in communications, teaching college English, and writing. His work has been published in The Christian Century, Washington Observer-Reporter, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, and Currents in Theology and Mission.

The Rev. Erik Hoeke is an ordained elder in the Western Pennsylvania Conference of The United Methodist Church and the director of continuing education at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Previously, Erik served United Methodist churches in Southwestern Pa. for 14 years. He earned a B.A. in English/journalism from Ohio Northern University, a master of divinity from Candler School of Theology in Atlanta, Ga., and a master’s in moral theology from Boston College. He currently serves on the board of directors for Jumonville Camp and Retreat Center in Hopwood, Pa., and has previously served on various boards and committees for the UMC and for nonprofits. Erik also has experience in communications, teaching college English, and writing. His work has been published in The Christian Century, Washington Observer-Reporter, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, and Currents in Theology and Mission.

Read Next