A Celebration of God’s Faithfulness

The word “Pentecost” comes from the Greek word pentēcostē, the feminine form of the word meaning “fiftieth,” as in “the fiftieth day” (hē pentēcostē hēmera). The festival was also called the “Feast of Weeks” (Exodus 34:22; Deuturonomy 16:9–10) because it was observed seven weeks (= a week of weeks) after the offering of the first fruits. Before Acts 2, Pentecost was a harvest festival, a celebration of God’s faithfulness as the lean winter season came to an end and families and communities began to bring in from the fields the food that would sustain them for another year.

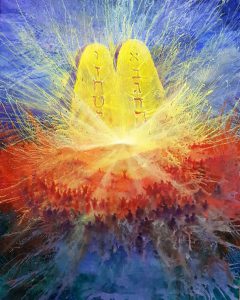

Still before Acts 2, Pentecost also became a celebration of the covenant between the God of Israel and His people and an occasion to renew that covenant. According to the book of Jubilees, a retelling of the story from creation to the eve of the covenant (Genesis 1–Exodus 19), the Feast of Weeks was associated with God’s oath to Noah never again to subject the whole earth to a flood (Genesis 8:21–9:17; see Jub. 6.4–16). It was also associated with the covenant between God and Abram (Genesis 15; see Jub. 14.1, 20) and with giving of Torah on Mt. Sinai (Exodus 19–31; see Jub. 1.1). The Lord summoned His people to gather before Him three times a year: at the Feasts of Passover, Weeks, and Booths (see Exodus 23:14–17). The Feast of Weeks was important enough that the apostle Paul, according to Acts, made his travel arrangements such that he would arrive in Jerusalem in time to celebrate Pentecost (Acts 20:16).

Pentecost, in other words, is not merely “the birthday of the Church.” Pentecost is an occasion to remember God’s faithfulness and provision and care—for His people in particular as well as for all humanity—in the waning of winter and the renewal of spring. And Pentecost is an occasion on which God has chosen to mark and mark again His commitment to His people and to all humanity, from the promise to one man that he would one day welcome a son of his own, to the establishment of one nation as the chosen people of God, to the promise to all creation that God would never again subject it to the cataclysm of a global deluge.

A Celebration of God’s Presence Among God’s People

Even before Acts 2, Pentecost was a day saturated with promise and celebration.

We are therefore not surprised to find that Jerusalem is full of visitors on this particular Pentecost. Jews from Parthia and Media in the east and Rome and Libya in the west and points in between (Acts 2:9–11) gathered not just to remember what God has done but also to celebrate what God is doing as the harvest starts to come in. As the sun crested over the Mount of Olives and began to illumine Jerusalem’s temple, expectations for the day were already high.

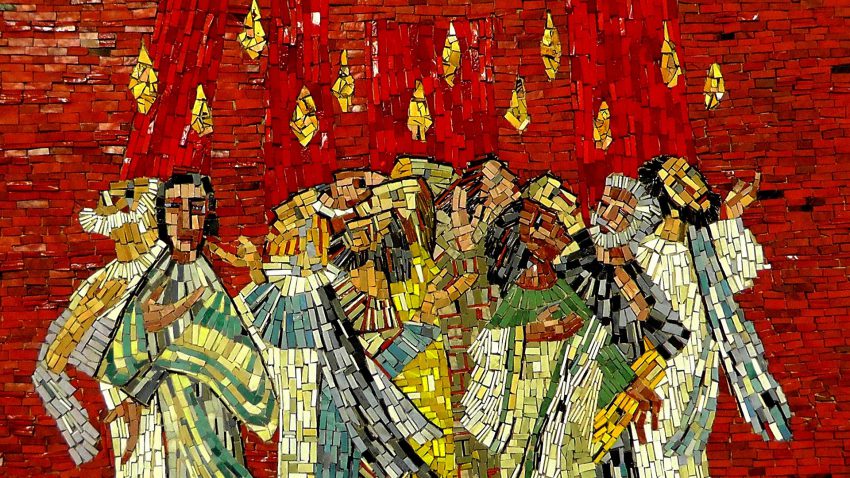

The Pentecost narrative in Acts 2 focuses on Peter’s proclamation of Jesus as David’s descendent and heir, the King of Israel, the Messiah. But don’t miss the background of that proclamation: the dramatic presence of God in His temple, among His people. The God of Israel had a history of dramatic entrances, from His descent onto Mt. Sinai (Exodus 19:16–19) to His taking residence in Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 8:10–11). Of course, God’s departure, described by Ezekiel, a prophet-in-exile, was just as dramatic (Ezekiel 10) and resulted in the destruction of the first temple by the Babylonians. A new temple was built 70 years later, but no stories were told of the presence of God inhabiting this new house. Now, in Acts 2, a dramatic sound, “like the rush of a violent wind,” fills “the entire house” (2:2).[1] Peter himself will connect the day’s dramatic events—roaring winds, fiery tongues, and bewildering speech—to a promise from the prophet Joel that God’s Spirit would be poured out “upon all flesh”: sons and daughters, old and young, regardless of social status (2:17–21, citing Joel 2:28–32).

In time, Jesus’ followers would find the place of God’s presence among His people, wherever they are. “Do you not know,” Paul asks Greeks in Corinth, “that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?” (1 Corinthians 3:16). First Peter agrees: “like living stones let yourselves be built into a spiritual house” (2:5). Jesus Himself was remembered to have promised, “Where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them” (Mattew 18:20). The failure of God’s presence among His people was broadly felt; the hope of the restoration of that presence was widely held. The story of Pentecost—for Christians, the first Pentecost, though the holiday had already been celebrated for centuries—is the story of God and humanity coming together again, a reconciliation made possible by Jesus and made certain by His resurrection from the dead.

In time, Jesus’ followers would find the place of God’s presence among His people, wherever they are. “Do you not know,” Paul asks Greeks in Corinth, “that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?” (1 Corinthians 3:16). First Peter agrees: “like living stones let yourselves be built into a spiritual house” (2:5). Jesus Himself was remembered to have promised, “Where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them” (Mattew 18:20). The failure of God’s presence among His people was broadly felt; the hope of the restoration of that presence was widely held. The story of Pentecost—for Christians, the first Pentecost, though the holiday had already been celebrated for centuries—is the story of God and humanity coming together again, a reconciliation made possible by Jesus and made certain by His resurrection from the dead.

A Celebration of God’s Renewal of Life

Today, in a post-industrial world, the new harvest does not have same cultural currency it had in the agrarian society of first-century Judaism and the earliest Christians. Global supply chains, processed foods, and refrigeration have weakened the perceived link between our food supply and the turn of the seasons. March and April might not have been the season for figs (see Mark 11:13), but who among us could not have found figs to eat near the vernal equinox? For many of us—not all of us, unfortunately, but many of us—our food supplies are secure enough that the start of the harvest no longer feels like the renewal of life itself.

But what about the presence of God with us, among us, within us, for us? Social science research confirms that many of us feel more disconnected from each other, from ourselves, from the world around us, and, I might suggest, from God Himself. This feeling of disintegration and disconnection is as real in the 21st century as it was in the first century.

My prayer for you, for me, for us, is that Pentecost would provide an occasion to lean into the promise of Immanuel, of “God with us.” May you, may I, may we experience the provision of God for us, not simply that He has given us what is needed for life but that God has given us His very self.

[1] All quotations from Scripture come from the NRSV updated edition.

Dr. Rafael Rodríguez, professor of New Testament at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, has taught New Testament for nearly 20 years. He serves on The Catholic Biblical Quarterly editorial board, the Life, Letters, and Legacy of Paul (SCJ) steering committee, and the Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus editorial board. Dr. Rodríguez is the author of The First Christian Letters: Reading 1 and 2 Thessalonians (Cascade, 2024), If You Call Yourself a Jew: Reappraising Paul’s Letter to the Romans (Cascade, 2014), and Oral Tradition and the New Testament (T&T Clark, 2014), among other works. His areas of expertise include the Apostle Paul, the Epistle to the Romans, the Epistles to the Thessalonians, Paul within Judaism, Second Temple Judaism and Christian origins, and social memory approaches to the Bible.

Dr. Rafael Rodríguez, professor of New Testament at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, has taught New Testament for nearly 20 years. He serves on The Catholic Biblical Quarterly editorial board, the Life, Letters, and Legacy of Paul (SCJ) steering committee, and the Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus editorial board. Dr. Rodríguez is the author of The First Christian Letters: Reading 1 and 2 Thessalonians (Cascade, 2024), If You Call Yourself a Jew: Reappraising Paul’s Letter to the Romans (Cascade, 2014), and Oral Tradition and the New Testament (T&T Clark, 2014), among other works. His areas of expertise include the Apostle Paul, the Epistle to the Romans, the Epistles to the Thessalonians, Paul within Judaism, Second Temple Judaism and Christian origins, and social memory approaches to the Bible.

Read Next